Last time, we left off discussing Aristotle’s conception of the good life and how it requires reason to achieve excellence. For Aristotle, there are two kinds of excellence within man. The excellence most often discussed by scholars is that of excellence of character:

Last time, we left off discussing Aristotle’s conception of the good life and how it requires reason to achieve excellence. For Aristotle, there are two kinds of excellence within man. The excellence most often discussed by scholars is that of excellence of character:

Excellence, then, is a state concerned with choice, lying in a mean relative to us, this being determined by a logos and in the way in which the man of practical wisdom would determine it. Now it is a mean between two vices, that which depends on excess and that which depends on defect; and it is a mean because the vices respectively fall short of or exceed what is right in both passions and actions, while excellence both finds and chooses that which is intermediate. (NE 1106b36-1107a5)

Excellence, then, is the mean between two extremes. Courage would be the mean between cowardice and bravado. If a solider is going to war, he ought to show courage. It is not virtuous if he cowardly deserts his post, but just as unvirtuous is the soldier who, full of bravado, jumps in front of bullets.

What I find so compelling about this account of the good life is that it matters both what actions you take and how you feel about those actions internally. In almost any other ethical theory, doing the right the thing is not linked to one’s own happiness or pursuit of the good life. For Aristotle’s conception of the good life though, these two things go hand in hand. Your ultimate happiness is only possible through acting virtuously – by doing the right thing, so to speak. What a novel idea!

If you’re curious, Aristotle does posit some very particular virtues. I don’t want to get in to a full discussion of them here, but I think they are interesting to look at, if only because some of them are not things we would normally think of as falling under the realm of ethics at all. Check out the list and see what you think:

- Courage

- Temperance

- Liberality

- Magnificence

- Magnanimity

- Right Ambition

- Gentleness

- Truthfulness

- Wittiness

- Friendliness

- Modesty

- Righteous Indignation.

All of these virtues are required to live the good life. Do you agree with the virtues Aristotle has on his list? Would you remove or add any of your own?

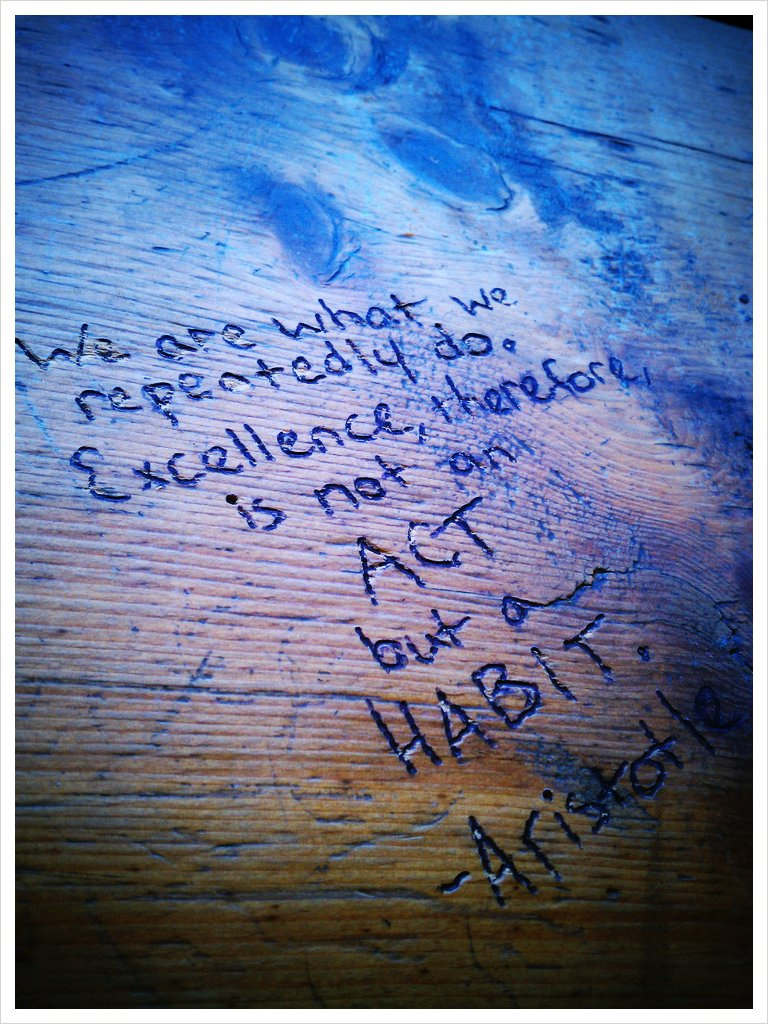

What makes this so different from other theories of the good life and even ethics, though, is how one goes about acquiring these virtues. Ideally, they should be taught to us as children so that they become habit. Because for Aristotle, excellence is habit. Part of becoming virtuous rests in perfecting one’s emotional response to situations. For example, simply refraining from theft does not make a person virtuous. If there is a constant struggle, if the person feels as if they are really missing out by not stealing, then even if they do not steal they cannot be considered fully virtuous. The person who has a virtuous character would have no desire to steal in the first place.

So if we are fighting with ourselves about whether to take some action, if we’re not sure what to do – then we may ultimately take an action that can be seen as virtuous, but this means we have not achieved excellence!

For me, a very real example of this is diet and exercise – which would fall squarely under the virtue of temperance. Excellence is not getting up one morning and going for a run. It’s not eating vegetables for dinner tonight. Even struggling to get better at these is not excellence. If I hate every minute that I’m eating better and exercising, I am not virtuous.

Real virtue is achieved when these actions become habit – when I get up and go run as part of my daily routine, and throw some vegetables on the stove without even thinking about it. Because it’s not just about taking the action – it’s about having the right emotional response.

Of course, the only way to get there is to repeat the actions over and over again. We learn what is virtuous by watching our role models and imitating their actions. In the beginning, it won’t be authentic. Current research shows it takes somewhere around 66 days on average to form a new habit. That means if you want to make a change – there’s going to be at least two months were it doesn’t seem natural and where you don’t want to do it. But you have to push through this. I experienced this in my struggle to give up soda. Thankfully my will power was enough to get me through it, and now drinking water is my new habit.

3 comments